Learning Quechua: The Basics, Legends, and Beliefs of Peru’s Most Common Indigenous Language

I have promised myself that my next post will be dedicated to the time spent with my parents, but right now I want to write about something that is fresh in my mind. I spent the last week in Huaraz, the regional capital of Ancash (about 2 hours from my town), studying Quechua. 4 days, 6 hours a day, alongside my fellow Ancash volunteers and taught by Orlando, one of Peace Corps’ finest. Orlando was born and raised in Huaraz, and has essentially dedicated his life’s work to preserving the Quechua language and culture. Across Peru, there are more than 80 indigenous languages and dialects. Over hundreds of years, many indigenous languages have disappeared, and many others are shrinking as we speak. Of those remaining, Quechua is the most widely spoken, and there are four variations: Central (what I am learning), Northern, Amazonian, and Southern.

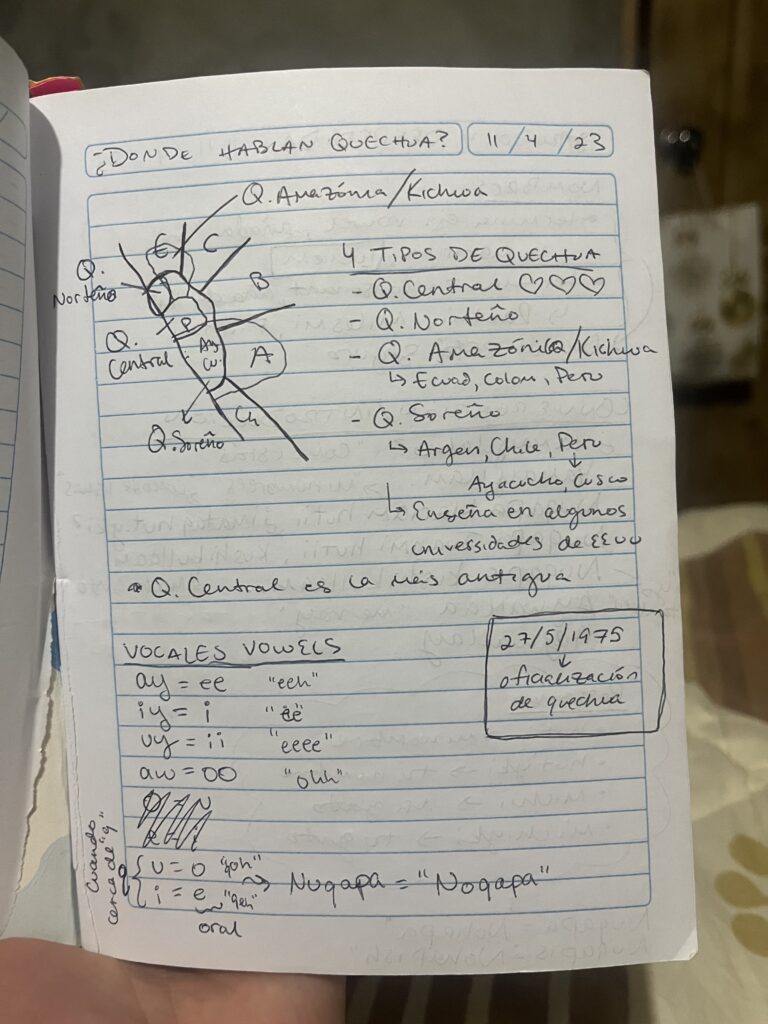

Quechua stretches from Argentina, Chile, and the southern Peruvian regions of Ayacucho and Cusco (all Southern Quechua), through Central Peru (Central Quechua, where I am), into the northwestern Peruvian regions (Northern Quechua), and finally reaching the northeastern Peruvian regions alongside Ecuador and Colombia (Amazonian Quechua, aka Kichwa). The language itself has so many distinct dialects that those who speak Ancash Quechua cannot understand those who speak Cusco Quechua. At this point, after so many years of separation, they are essentially different languages. (See the picture for my first ever Quechua notes!)

Part of being a volunteer in Ancash means learning Quechua. Since the day we were assigned our sites in pre-service training (PST), the 8 of us began weekly Quechua lessons with Orlando. Every Saturday, we would come into the training center for 4 hours to learn the history and basics. Once in our sites, we could take it upon ourselves to find our own Quechua tutor, for which Peace Corps would reimburse us. So, since March, I have been taking weekly lessons with a Quechua tutor in the nearby town of Caraz.

In Pueblo Libre, essentially the entire population speaks Quechua. Almost everyone also knows Spanish, and everyday I am surrounded by both. In the health post, appointments are many times done bilingually. The patient speaks Quechua, and the medical professional responds in Spanish. Despite speaking in different languages, the two understand each other, and it is a fascinating thing to see. The house visits I attend to mothers and pregnant women are also almost entirely in Quechua. While volunteers in non-Quechua speaking sites may be able to contribute more to house visits, I essentially turn them into a Quechua-learning opportunity. And, it has paid off. Each week, my Quechua is advancing. I am still at the stage where I am too shy to really speak it, but I know enough basic phrases that I blow the socks off of any man or woman that has never heard a gringa speak their language. And really, I see their eyes and energy change when I speak it. I truly want to learn it, and I can see that it means a lot to them.

The language itself is unlike anything I have ever heard. It is mostly a spoken language, so you’ll never see signs in Quechua, and native speakers have a hard time spelling something out if I ask them (so I’ve just given up on that front). Here are a few examples:

- Nuqapa Luciem shutii. = My name is Lucie.

- Nuqa Estados Unidospita kaa. = I am from the United States. (you’ll find a lot of Spanish/Quechua mixing)

- Ayka watayuq kanki? = How old are you?

- Nuqa akata mikuyta munaa. = I want to eat guinea pig.

- Qam inglesta palanki? = Do you speak English?

Little by little, I will learn the language. By the end of 2 years, I hope to be able to chat with all the old ladies here.

In terms of Quechuan culture, it is full of color, legends, family, superstitions, and food. If you hear an owl hoot, or the fruit tree behind your house gives a lot of fruit one year, that means someone is going to die. In June, you’ll see people burning parts of the mountainside to call the rain. When someone passes away, you lay their clothes out on a table to welcome their spirit back inside their home. Today, our last day of Quechua class, and my first day back in Pueblo Libre, was full of ancient tales. Orlando sat us down for half an hour and retold ancient stories: The Achikay – basically Peru’s Hansel and Gretel; Qilqa – a godmother that has an affair with the father and who’s head ends up bouncing around town (some things may have been lost in translation there); and my favorite, The Pishtaco – a gringa/o that goes around cutting Peruvian’s body parts and taking the fat (to do what with, I didn’t quite catch). I had heard of the Pishtaco legend before in Pueblo Libre, and how many children are afraid of white people, as they assume they’ve come to cut them up and steal the fat off their bones. I’m hoping I’ve proven to the kiddos that I am not here by such motives.

Tonight, after coming home from my week away, I sat at the dinner table with my host parents and went over my Quechua notes. They corrected everything to Pueblo Libre Quechua, as even some words and phrases change between Huaraz and here. Naturally, we began sharing the Quechua stories we know, and they recounted their experiences with almas (spirits) in their lifetime. Once many years ago, Yoli (my host mom) was walking home when she saw a white figure, which she knew was a spirit. She remembered what her mother had always told her: if you come across a spirit, sing and nothing will happen. So, that night, Yoli sang all the way home.

She recounted another story, which reminded me so much of my Oma. When she was 8 years old, Yoli’s grandfather passed away. So, as the custom goes, they put a set of his clothes on the table one night to welcome his spirit back inside. Yoli and her cousins slept on the floor that night, beneath the table. They were as quiet as can be, as it is known that the spirits get scared if too many people are nearby. In the middle of the night, Yoli remembers seeing the door open, and her grandfather walk in, arms bent at a 90 degree angle at his sides, palms up. He walked past all of the children, brushing his hand across them as he went. Yoli was scared to death. I couldn’t help but think of “The Crooked-Foot Man”, a legend Oma used to tell us in the dark basement. Once the story reached its peak, a banging on the window would commence and we would hear the dragging of a limp leg outside. The bravest of us would run outside to catch The Crooked-Foot Man, to no avail. While we always suspected it was Opa outside, we never caught him. And we were always so darn scared. Now, I’m not saying it was Yoli’s grandmother playing with them, and I certainly would never propose that idea. But either way, it reminded me of my own childhood, scared as can be alongside my cousins.

Across Peru, Quechua-speakers have faced a lot of discrimination as it is associated with more rural, poorer, areas. Check out this 2017 Economist article to see how the Peruvian government has tried to reverse the stigma – including testing grade school teachers to ensure they have a basic knowledge. Multiple times, I have been told my teachers at my school that I speak more Quechua than them. My host aunt, who is fluent in Quechua, also wants to review my written Quechua notes, as she is pretty rusty in that realm (like I said, it is a mostly spoken language). One of my favorite things is whipping out some Quechua in the classroom. My students always go wide-eyed.

8 thoughts on “Learning Quechua: The Basics, Legends, and Beliefs of Peru’s Most Common Indigenous Language”

Fascinating background of Quechua, and wonderful that you’re learning and speaking the main indigenous language.

Thanks Poppers! Glad you got to hear a bit of it when you came out

Lucie-

Fascinating! Thanks for sharing the Quechua phrases. You know I’ll eat damn near anything but I’ll need to be able to say, “I don’t want to eat Guinea Pig” before my visit. We’ll need to work on that, OK?

Hello! That would be: Manam, nuqa hakata mikuyta munaatsu.

Start practicing

Great Post!! I love hearing about the local stories and customs. Please share more in the future on these topics.

I say your dads photos and posts on FB. Looks like you had a GREAT visit. I even googled searched the largest city with no roads in. I learned something new. I know your parents must be so proud of you. Peace Corps truly is the “toughest job you’ll ever love”.

You’re almost a year in, and as a bystander the time has really zipped past. I’ve throughly enjoyed following your blog. I hope the next year provides even more opportunities to learn and grow as you navigate language and cultural experiences in Peru. Your doing a great job sharing these experiences with those of us sitting here on the sidelines watching and learning through you.

My daughter Claire is still half way through PST. She had a site visit to her location 2 weeks ago. She will be living at a Catholic convent with the Nuns. She will have her own home (livingroom, kitchen, bedroom – more of a closet with a matress, bath area, and latrine. Only $22 a month in rent. As a non Catholic, she is really looking forward to the extra cultural experience of the convent. No one speaks English in her future site, only the local language of Kirawanda (not sure of that spelling). She says it is very difficult to learn as every word has 6 or 7 syllables, and they all sound the same. She has been keeping an oral diary which she records on Messanger, and then shares with us. So far, I have throughly LOVED her stories. Claire has a dark sense of humor, where she can find the “funny” in the most difficult situations. We (me, my daughter Devyn and my sister Robin – 3x PCV Paraguay, Ghana, and Uganda) are hoping to visit in fall of 2025. I hope to have a visit as enjoyable as your parents.

Looking forward to your next post. Thanks again for sharing your experience.

Hi Holly, yes the time has certainly flown and I am so happy my parents got to see my life here. And I hope you get to do the same with Claire! That’s sweet he gets her own home. Every country operates differently – in Peru, it’s mandatory that we live with host families. Also great that she will be forced to learn the local language. There’s no more efficient way to learn than having no choice.

So wonderful to read your posts. Sorry I’m a few days out but we had your parents and Duncan and Whitney and Andrew, PCV Cameroon and State Dept. here at the lake!! Great time had by all!!

I applaud your efforts to learn beyond the Spanish and Quechua!! It does make a huge difference to speak to people, especially when it’s about their healthcare, in their native language. I spoke, or tried to speak, 3 languages, in The Gambia, and none of them, at that time 45 years ago, were written and all so different!! My Mandinka is still with me a bit but the others, besides greetings, have flown from my mind!!

I continue to love your posts and am so proud of you!! You have the biggest smile ever and I am sure you have endeared everyone to you. Bless you, Lucie!! Love you.

Hi Sally-Ann, so good to hear from you! I’m sure everyone had a blast at the lake. Thank goodness I came in with an intermediate Spanish level, and only have to learn 1 local language … I can’t imagine 3. I do hope that the Spanish sticks with me forever. The Quechua, I don’t think I’ll be using much back in the states, so we’ll see how much I remember in 30 years. Love ya!